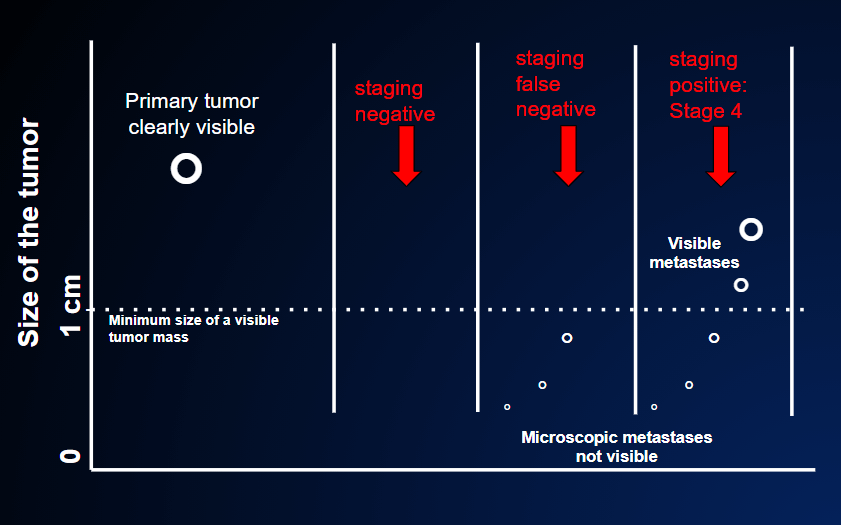

The risk of relapse is assessed when preoperative staging yields a “negative” result (i.e., a good outcome, as no distant metastases have been found), and surgery or other local therapies have completely eliminated the cancer: and so, when the patient has, hopefully, been cured.

But if the patient has been cured, why “evaluate the risk”? The risk of what? And why should we consider other therapies after the surgical operation?

The answer lies in the fact that cancers tend to metastasize. This is the main danger, as it is through metastases that cancer kills.

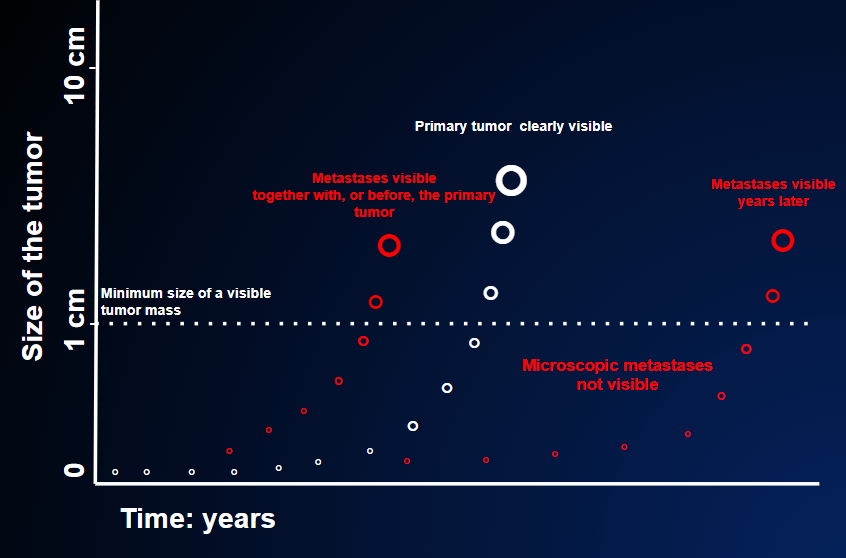

Metastasis is a fairly unpredictable phenomenon. In general, it takes place when the cancer is advanced, but sometimes happens at the same time as the tumor appears. (FIGURE 2) (ONLY CHEMOTHERAPY OR OTHER MEDICAL THERAPIES)

In the second case, the staging result is falsely negative because although the CT, PET scan and magnetic resonance tests are negative (=no tumor in other organs) the primary tumor has already spread outside the local origin, but these small nodules are too small to be revealed by the imaging tests . These tests usually disclose nodules of at least 0.5-1 cm ( the dotted line in the figure). After the primary tumor is removed, the patient is not cured. A relapse will become known when these small nodules have grown above that threshold.

In the third case, the staging result is positive (= presence of cancer in other organs ) because metastases are already seen by the staging tests: they are already large enough at the time the primary cancer is discovered.

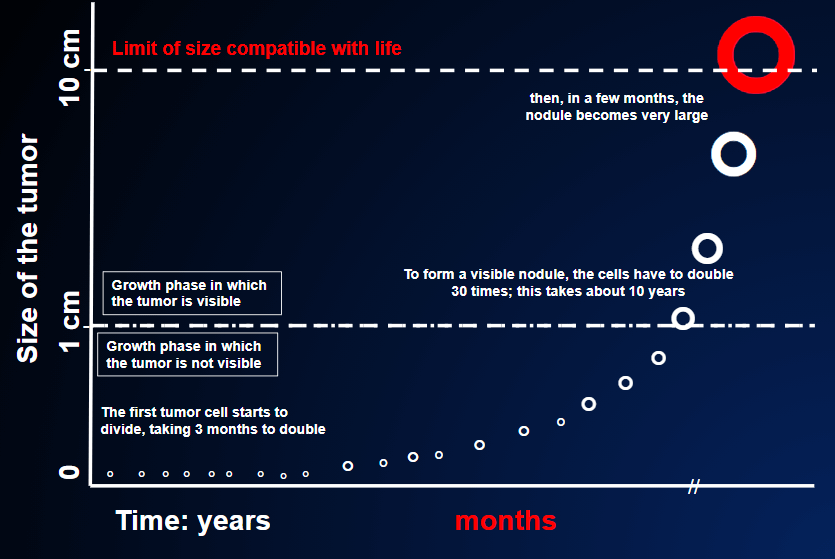

To understand this, we need to remember that a small, hardly visible, tumor nodule of 1 cm (whether it is the primary tumor or a metastasis) contains about 1 billion cells; to reach this number, it may have taken 5, 10 or 20 years (HOW LONG HAS THIS TUMOR BEEN THERE?) (FIGURE 7)

The tumor is far more likely to spread metastases when it is much bigger than 1 cm. Sometimes, however, metastases can detach from the primary tumor much earlier, during the long period of development of the tumor (FIGURE 3).

This means that micrometastases might already be present, even though they are not visible during preoperative staging and the tumor mass has been completely removed (R-0) during the surgical operation. In 6 months or 1 or 2 years, these micrometastases might turn up in various organs, making the case incurable.

Indeed, it is this phenomenon that makes tumors so fearsome: even when they have been eliminated, we cannot be sure that the patient has been cured, as the tumor may have spread metastases before it was removed.

So, to answer the three questions above, we can say:

- Risk of what? The risk is that metastases may have spread from the tumor before it was removed. If this has actually happened, and if no therapy is administered, the situation will be dramatic: instead of being “cured” by the surgical operation, the cancer will now have become incurable, though neither the doctor nor the patient will be aware of this.

- Why “assess the risk”? Assessing the risk means considering several factors reported by the pathologist who examines the surgical specimens; these factors help us to estimate the probability of there being micrometastases, which are not yet visible and which could cause recurrence of the disease. This process of assessment may also require molecular examinations (more complex examinations that are carried out on the surgical or biopsy specimens already taken), which can help us to estimate the risk more precisely. Often, these sophisticated tests can also indicate which therapy would be most effective against any micrometastases; they can therefore help us to decide whether to administer adjuvant therapy and, if so, which therapy to administer.

- Why should we discuss whether to administer other therapies after the surgical operation (so-called adjuvant therapies)? If there is a risk of relapse, and if this risk can be eliminated by means of treatment, why do we need to discuss it? Let’s just do it. Well, unfortunately, it’s not as simple as that. Indeed, adjuvant therapy doesn’t work in all tumors. Moreover, even in tumors in which it has proved to be effective, its effect is far from perfect; adjuvant therapy can never eliminate the risk of relapse completely. In other words, when the doctor proposes adjuvant therapy, it is because it can reduce the risk of relapse, though it can never eliminate this risk completely.