The circumstances in which adjuvant therapy is administered are very particular:

- We are fighting an invisible enemy; indeed, we don’t even know if it is there.

- We have no way of knowing if it is working while it is being administered.

- The only way to ascertain its effectiveness is to wait for a sufficiently long time (generally 5 years) without disease recurrence.

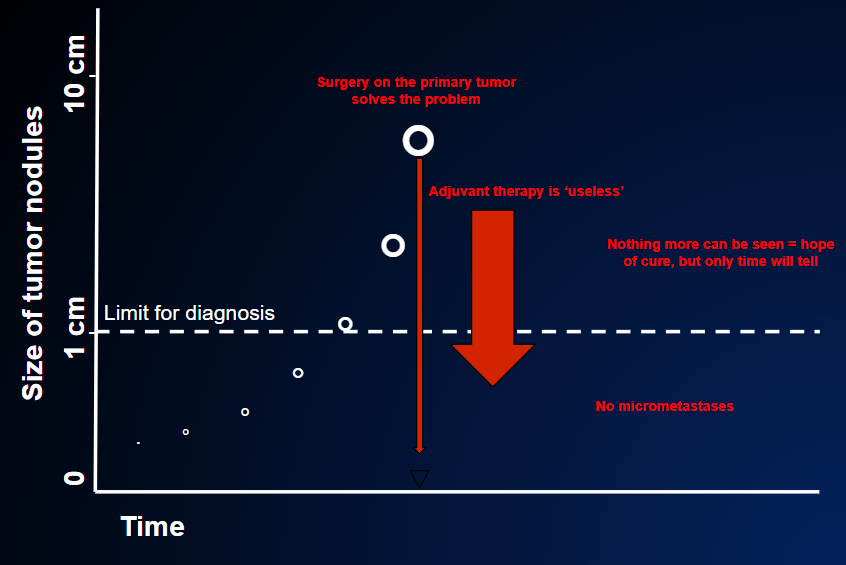

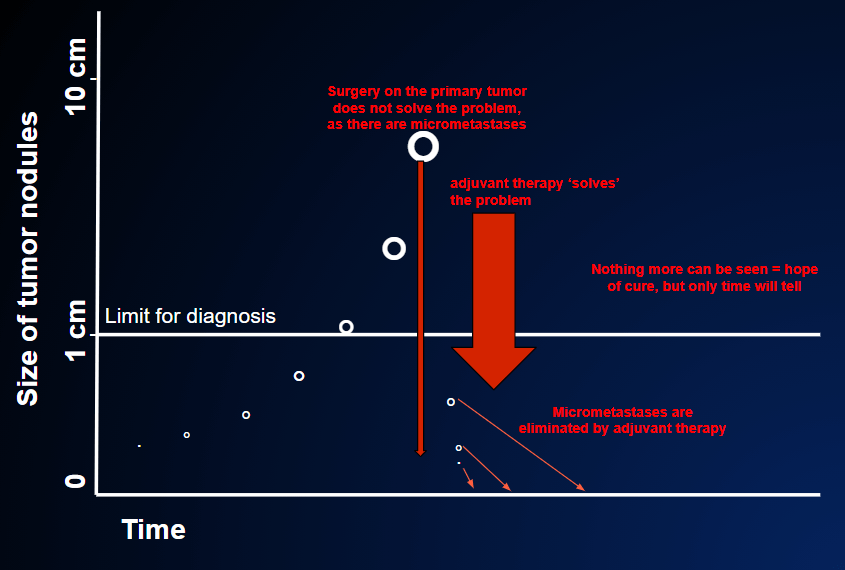

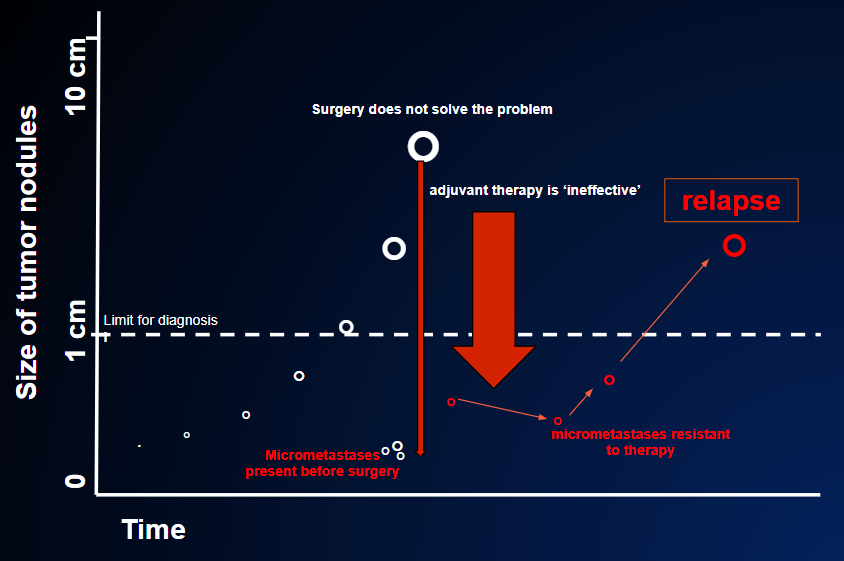

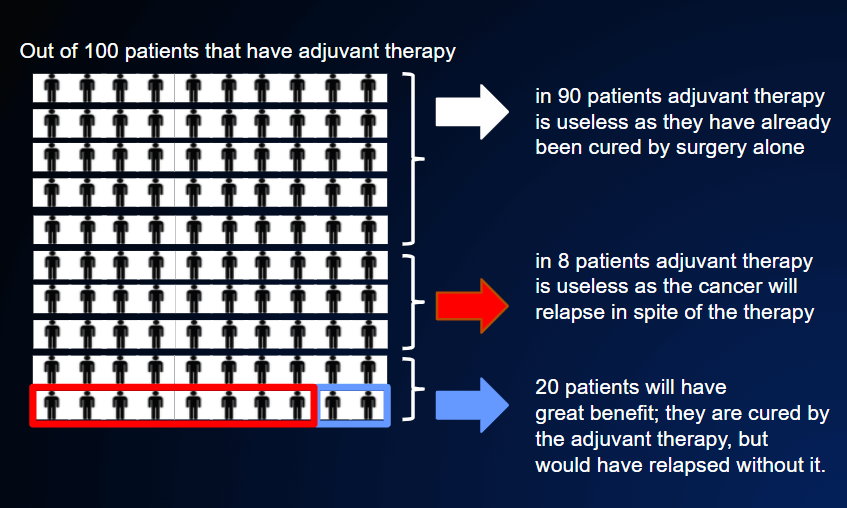

- Finally, we will never know whether the therapy has been administered unnecessarily, in that there may never have been any micrometastases (and, in reality, surgery was enough to cure the disease) FIGURE 9; or whether the patient has been cured thanks to the adjuvant therapy administered FIGURE 10, or not, as in FIGURE 13.

Fig 13 The white circle indicates the primary tumor that has already spread metastases at the time of surgical intervention ( the long thin red arrow). In this case the residual cancer cells are resistant to adjuvant therapy; they will grow despite adjuvant therapy and the disease will relapse. Unfortunately today it is not yet possible to predict if adjuvant therapy will work, as in the case of fig 10, or if it does not work, as in this case.

Having decided to administer adjuvant therapy, we need to “start in time”. Indeed, we must remember that the aim of this therapy is to eliminate any micrometastases. Clinical studies have demonstrated that, in cases in which adjuvant therapy is effective, it should be started within about two months of the surgical operation. This is logical, in that chemotherapy may be less effective against larger tumor masses, and may not be able to eliminate them completely if they have grown beyond a certain limit.

In general, then, adjuvant therapy is started between 3 and 10 weeks after surgery; starting sooner than this has not been seen to improve its results.

The duration of adjuvant therapy is fixed; it usually lasts between 3 and 6 months, as in the case of chemotherapy. The duration does not depend on the results of any intermediate assessments, as there is nothing we can assess during the course of therapy.

By contrast, in the case of adjuvant therapy with hormones or antibodies (breast or prostate tumors, melanomas etc.), the treatment may be continued for many months, or even years, as the side-effects of these treatments are generally much lighter.

Subsequently, once therapy has ended, the period of follow-up begins, during which periodic examinations are scheduled.

It is very difficult to say how much benefit adjuvant therapies bring in the various types of tumor. The table reported in POSSIBLE PREVENTIVE THERAPY AFTER SURGERY shows very approximate estimates of the increase in the percentage of patients cured, in comparison with surgery alone, in the various types of tumor.

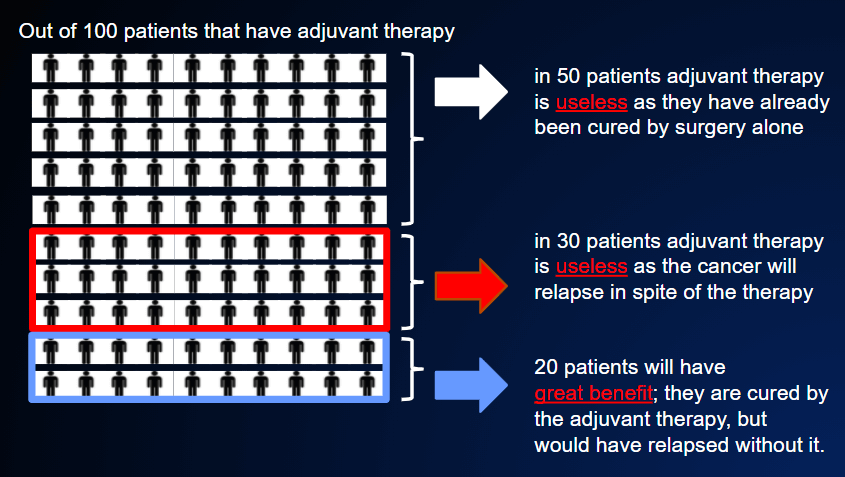

However, within each category of tumor shown in the table, the benefit will depend on the risk of relapse. Thus, if the risk is high (50%), the benefit may also be great (20% or more), FIGURE 8;

by contrast, if surgery has been carried out in the initial stage of disease with low risk (10%), the benefit will be no more than 1-2%, FIGURE 11.

Unfortunately, this means that estimates of the average risk and benefit do not help us to take decisions regarding the individual patient; the decision must therefore be “tailored” to each single patient.

The balance between risk, benefit and side-effects is highly subjective.

This means that, to some patients, a 20% probability of disease recurrence may be regarded as an unacceptably high risk, and a 2-3% reduction in this risk may be seen as precious, despite the possibility of toxic side-effects. Other patients, perhaps more fatalistic, may be prepared to accept a post-operative risk of 30%, and refuse preventive therapy if the benefits are not at least 3%, 5% or more.

Experience shows that these examples are very real. For this reason, it is very important for the doctor to be aware of these estimates and to be able to communicate them to the patient, in order to decide together what is best for that individual.