A diagnosis of cancer is serious and, before pronouncing the word, we need to be absolutely sure.

Often, people’s fear of cancer is based on very few findings. Obviously, these people are oppressed by anxiety. In many cases, their fear is fully justified, in that the suspicion becomes a certainty. But in many other cases, this does not happen; after a period of anxiety, which may be more or less long, and after undergoing diagnostic examinations, which may be more or less complex, the patient emerges reassured, as the findings that originally gave rise to suspicion turn out to have been due to a non-malignant condition.

These fairly frequent situations are typical of the phase of “diagnostic suspicion”. It is a particularly delicate phase, in which the patient is kept “hanging on” (not knowing whether “it is or it isn’t”). It is also the phase in which doctors may make the greatest mistakes. On the one hand, if they reassure a patient who complains of some disorder and then discover a few months later that the cause was a tumor, it may mean that they reach the diagnosis too late. On the other hand, talking of cancer without being sure of the diagnosis would have a devastating psychological effect on anyone.

It is therefore extremely important to know when further tests are needed in order to reach a diagnosis and when, instead, it is right to reassure the patient.

How can we distinguish between these two conditions during the phase of diagnostic suspicion?

In medicine, the doctor must consider 4 dimensions in order to make a diagnosis:

- what the patient says;

- what the doctor finds during the physical examination;

- blood tests results, and

- what the instrumental imaging examinations (radiological/endoscopic) show.

In oncology, there is also a fifth dimension which must almost always be taken into account, as it gives certainty to the diagnosis: the biopsy (see definitions on p. 2). This enables a tissue sample to be analyzed under the microscope, to conclude whether or not there is cancer, and, if there is, what type it is.

Not always, however, are all 5 dimensions necessary. In many cases, the presence of symptoms, or abnormal findings during the physical examination (swollen lymph nodes, nodules, blemishes on the skin, etc), or abnormal blood test results or radiological findings can, indeed must, be completely ignored when they obviously constitute no danger for the patient. In other cases, it is necessary to carry out a lot of other examinations and to take a biopsy in order to eliminate all uncertainty.

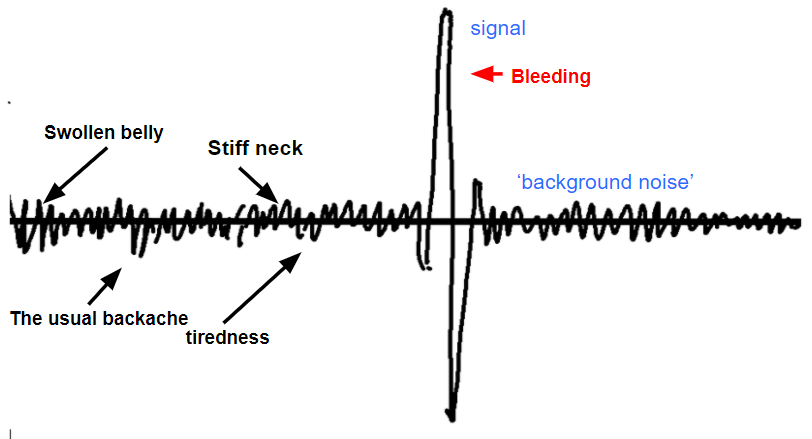

How do we decide whether to reassure the patient or to investigate further? The answer lies in the type, intensity, duration and evolution of the disorder or abnormality. Indeed, each of the 4 “dimensions” of the diagnosis, as described above, may display a certain amount of “background noise”; in other words, there may be small variations from the normal range even when the patient’s organism is absolutely normal FIGURE 1.

For instance, a swollen lymph node, a subcutaneous nodule or a blemish on the skin does not, on its own, mean anything. The same can be said for being “a bit more tired than usual” or having “a bit of a headache” when the patient has suffered from headaches for years. Likewise, the finding of “micronodules” on the chest x-ray does not mean lung cancer by any means; it is a very common finding during chest x-ray examinations.

Only when each of these indicators of possible disease displays a particular intensity, duration and evolution do we need to worry.

For instance, a hard, irregular lump in the breast that has not previously been noticed requires investigation, as it is a clear alarm signal; it is not background noise, as, for example, a soft nodule that has remained the same for years. With regard to symptoms, moreover, some must always be treated as alarm signals, regardless of their duration or evolution (THERE ARE WORRYING SYMPTOMS). For example, any bleeding from the digestive tract or the urogenital apparatus always requires attention in every case. The patient may well have simple hemorrhoids (sometimes called “piles”), uterine polyps or cystitis (inflammation of the bladder), but bleeding is a very precise signal that must not be neglected.

Finally, there are situations in which all 4 dimensions of the diagnosis provide important, converging signals, so much so that there may be no need to perform a biopsy to confirm something which is already “certain”. Such cases are fairly rare. However, in elderly patients or those who are very sick, or if the disease is in an advanced stage, the most appropriate choice may be to avoid performing a biopsy.