Some time after the beginning of therapy (usually 2 or 3 months), the efficacy of the therapy is assessed in three ways: through physical examination, imaging tests and, in certain cases, tumor markers.

Physical examination is the first way to assess the patient’s condition. If the patient initially had symptoms caused by the tumor, and these symptoms disappear after some weeks of therapy, this is a very strong indication that the therapy is working, regardless of the results of the other tests. If, on the other hand, the patient did not have symptoms at the beginning of treatment, the physical examination will not tell us whether the therapy is working or not – unless the patient complains of new symptoms that are not due to side-effects of the treatment.

In this latter case, it is probable that the tumor has increased in size, which means that the therapy is not working.

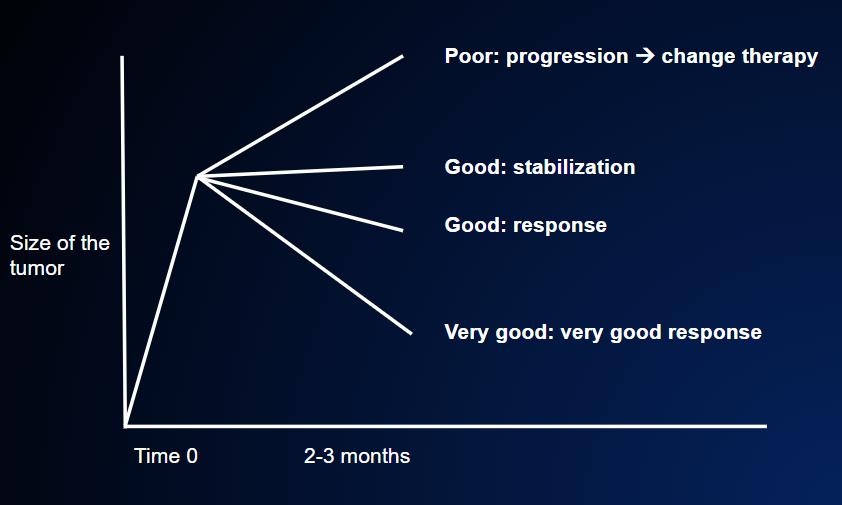

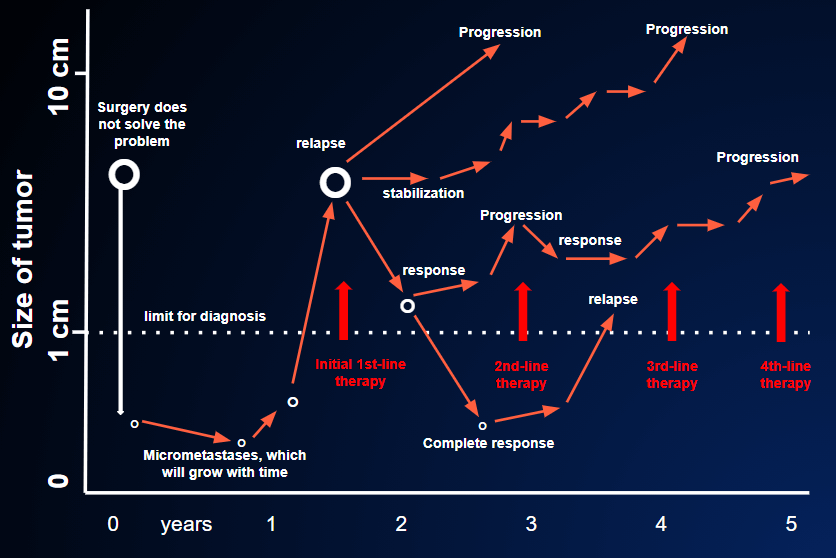

The second way is to perform imaging tests: generally CT, PET, magnetic resonance, echography and scintigraphy. These tests are first performed before the beginning of therapy, and are repeated after 2-3 months of therapy; the two sets of images are then compared. If the metastases have decreased in size, we can say that the patient is responding; if they remain unchanged, the disease is said to be stable. However, if the metastases have increased in size, it means that the disease is progressing. FIGURE 18

The third way is to measure tumor markers. (FOLLOW-UP) If the tumor is one of those that produce so-called tumor markers (such as CEA, PSA, CA19-9, CA15-3, CA 125, alpha-fetoprotein, etc), a reduction in the level of these markers is a favorable sign, while an increase is an unfavorable sign. It must be pointed out, however, that these markers are of limited reliability and are generally used only as a support for the other two methods of assessment.

With regard to tumor markers, two important features have to be considered: their level, and how this level changes over time. A marker that steadily rises over a series of three or four consecutive assessments is a fairly convincing sign of disease progression. This sign will be even stronger if the absolute level of the marker is very high (a value of hundreds or thousands instead of units or tens); for example, an increase from 5 to 7 is not significant, while an increase from 5000 to 7000 is much more significant, even though the proportion of the increase is the same.

When judging whether the therapy is working or not, we need to consider the above-mentioned three indicators in descending order of importance: in first place, any improvement in symptoms (if present); secondly, the results of CT and other imaging tests, and finally, tumor markers.

Nevertheless, there are some situations in which a tumor marker is the only indicator of disease; in such cases, it is the only way to judge the efficacy of treatment. This occasionally happens in tumors of the breast (CA 15-3), ovary (CA 125), colon (CEA), pancreas (CA19-9) and prostate (PSA), in which the respective markers may be increased even if imaging tests fail to detect the presence of disease.

In the advanced stage of cancer, the decision to begin treatment on the basis of increased tumor markers alone generally stems from the patient’s anxiety, which prompts the oncologist to start therapy even if “the tumor is not yet visible”. This anxiety is fully justified. Indeed, despite the limits of tumor markers, a steady increase in their levels – in certain conditions (high risk) – is a very strong indicator of disease relapse.

At the same time, however, there is general agreement that “treating the marker” is not a good medical practice. Medical decisions must also take into account psychological factors, and so beginning treatment on the basis of increased markers alone may be regarded as “acceptable”. However, it is not recommended, as starting therapy earlier on the basis of markers yields no greater benefit than starting therapy when imaging tests reveal metastases.

Once the patient has been reassessed, we can say whether the disease has:

- decreased (the patient is responding);

- remained unchanged (stabilized);

- or increased (disease progression): the tumor is resistant to the therapy and continues to grow, FIGURES 17, 18.

Obviously, if the tumor has responded to treatment (i.e. has decreased), the future prospects are much better than in the other two cases. This good news understandably brings great relief and gives patients new strength to continue their therapy.