There are 5 reasons why this may happen.

- In certain types of tumor, clinical studies and the experience of specialists have shown that the probability of relapse and death is the same whether adjuvant therapy is administered or not. Clearly, in such cases, adjuvant therapy will not be proposed. In tumors of the kidney, for example, radiotherapy has been seen to produce worse results than doing nothing at all. Moreover, chemotherapy has no beneficial effect, and, more recently, even biological therapies administered for long periods have failed to show any advantage over surgery alone.

- Rare forms of some common types of tumor exist. For instance, while preventive chemotherapy has been clearly demonstrated to be beneficial in infiltrating ductal and lobular tumors of the breast (the two most common breast tumors), the same cannot be said of other, less frequent, forms (the various forms are distinguishable under the microscope). Indeed, in the case of tubular carcinoma of the breast (rare), the advantages of preventive chemotherapy are minimal, which makes it useless in most cases. Similar examples can be found for every type of tumor, which complicates things enormously.

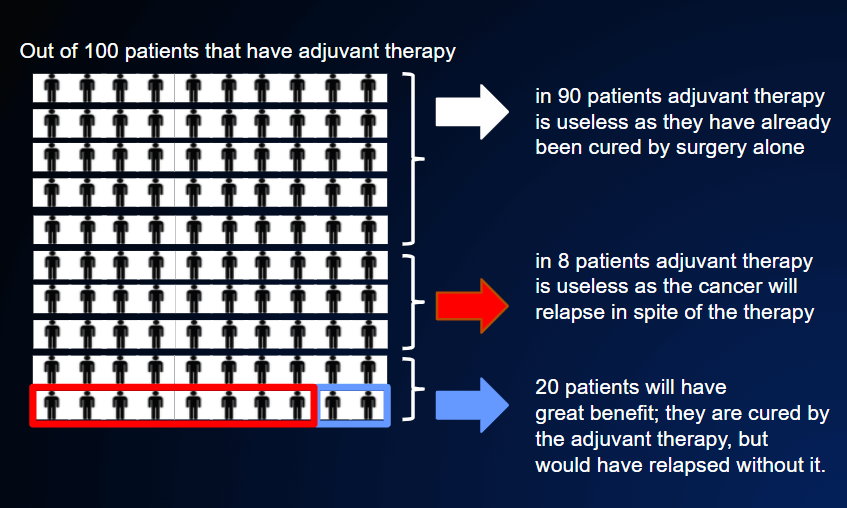

- The most frequent cases in which adjuvant therapy is not prescribed are those in which both the risk of relapse and the benefit of the therapy are low (ADJUVANT THERAPY), for instance, if the risk is around 10% and the benefit around 1-2%, as in FIGURE 11.

In other words, 100 patients would need to be treated in order to “save” 1 or 2. Ninety would already have been cured by surgery, while 8-9 would undergo therapy in vain and would relapse. Clearly, no problem arises if the adjuvant therapy in question is hormone therapy, which is very well tolerated. However, in the case of toxic chemotherapy, which can cause damage that may even be permanent, we are forced to ask ourselves if it is worth it.

Psychology experiments have demonstrated that a healthy person, when faced with this situation of a very meager balance, will generally say “no” to therapy.

In the case of a sick person, however, the answer is much more uncertain. Indeed, about one third of patients opt for therapy, even if it is toxic, in order to obtain a very small benefit (1-2%); another third would undergo therapy only if the benefit were of 3-4%, while the remaining third, the most fatalistic, would accept therapy only in exchange for a benefit of at least 4-5%.

4. The case of elderly persons involves other important considerations:

- a healthy 60-year-old has about a 92% probability of being alive and well at the age of 70 years;

- healthy 70-year-old has about a 75% probability of being alive and well at the age of 80 years;

- a healthy 80-year-old has far less than a 50% probability of getting to 90.

These figures have an important impact on the choice of whether or not to administer adjuvant therapies after cancer surgery. Indeed, as we have seen, the benefit of such therapies varies from 0 to 30%, with an average of about 5-15% (POSSIBLE ADJUVANT (PREVENTIVE) THERAPY AFTER SURGERY). In elderly persons, and especially in the very old, the risk that adjuvant chemotherapy will have fatal toxic effects is at least tripled. As a general rule, therefore, adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended in the elderly only when the risk of disease recurrence is high and the benefit of therapy is at least 5-10%.

5. Similar reasoning is applicable to patients who, in addition to the tumor that has been surgically removed, have other serious diseases that reduce their life expectancy. Indeed, we must always consider the whole person, not just the tumor. Moreover, before taking decisions on therapy, we must consider not only the presence of other diseases, but also the patient’s psychological condition.

Even if no adjuvant therapy is administered, the patient will still be followed up in the same way as if she/he were on therapy. Indeed, the situation is similar. Periodic examinations are carried out to check that there has been no relapse. Obviously, simply performing these examinations (CT, blood tests, scintigraphy, etc.) does not reduce the probability of relapse; however, if the results are favorable, the patient will be reassured.