Follow-up is the long period that begins after the surgical operation or after any adjuvant therapy is administered. During follow-up, examinations and tests are carried out at regular intervals (every 4-6 months for about 5 years) to check that all is going well or, by contrast, to detect any signs of relapse before the patient has any symptoms.

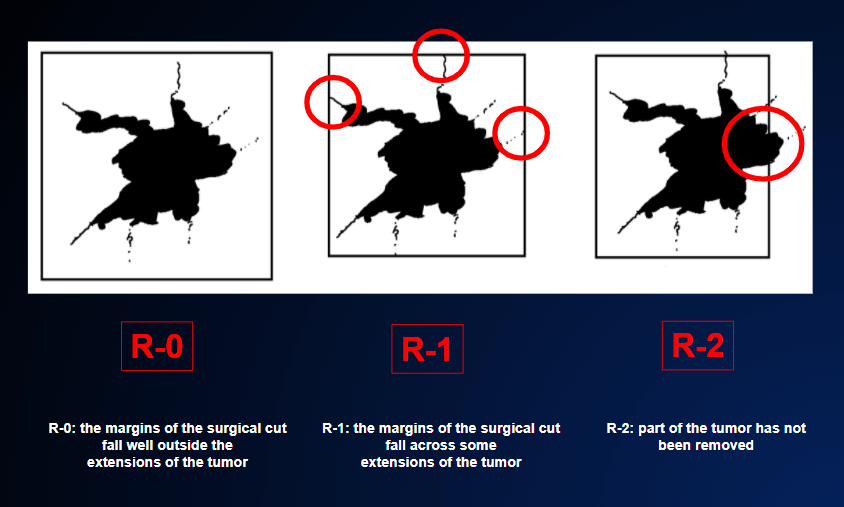

If the surgical operation has been radical (i.e. the whole tumor has been removed) and the pathologist has confirmed under the microscope that the margins of the specimen removed are “clean” (i.e. no tumor residue has been left behind: R-0 surgical result), FIGURE 6, the patient is on the way towards being cured.

In such cases, each follow-up visit will reassure the patient.

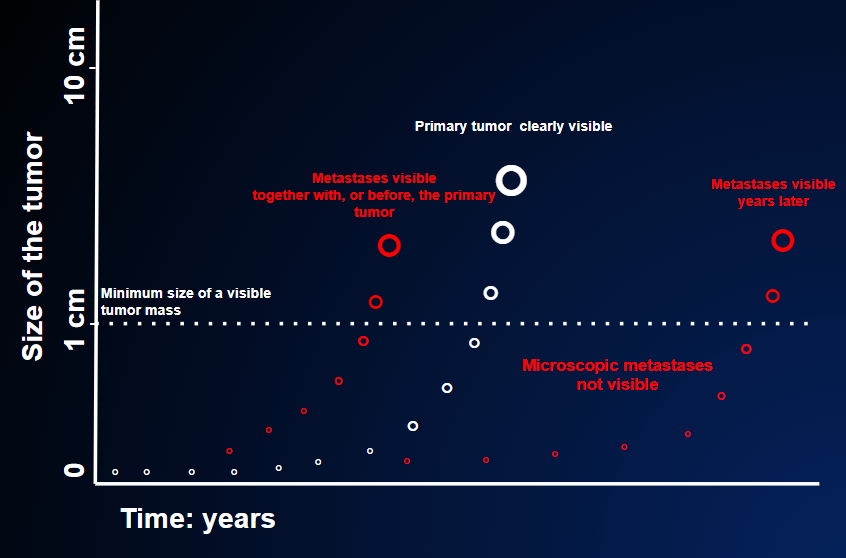

Nevertheless, even in the favorable conditions described above, some risk remains, even if adjuvant therapy has been administered. Indeed, some tumor cells might have been spread to other organs before the tumor was removed, giving rise to metastases over time. The follow-up examinations can detect these early signs of disease relapse, FIGURE 3.

The examinations commonly carried out during follow-up include:

- blood tests;

- instrumental imaging examinations;

- physical examinations.

1.Blood tests are used to find out whether the various organs – liver, kidney, bone marrow, etc. – are working properly. Among these blood tests, tumor markers also have a certain importance.

Tumor markers are proteins that are produced by tumors. Their importance is obvious. A sample of blood is taken; if the marker is detected in the sample, presumably there is a tumor; if the marker is absent, presumably there is no tumor.

Unfortunately, however, it’s not as simple as that; if it were, the entire healthy population could be screened for these markers, tumors could be diagnosed as early as possible, and an extremely high percentage of patients would be cured by surgery alone. But that’s not the way it is. Indeed, many tumors do not produce markers, while many noncancerous conditions can raise the level of these markers even if there is no tumor.

For this reason, tumor markers are used during follow-up only as an aid to the diagnosis of the presence or absence of relapse. It is therefore highly unlikely that anti-tumor therapy will be started simply because tumor marker levels are raised; further evidence is needed, such as the presence of disorders or symptoms, or the appearance of new nodules on imaging tests (HOW AND WHEN CAN WE ASSESS THE EFFICACY OF THE THERAPY?).

With regard to tumor markers, two important features have to be considered: their level, and how this level changes over time. A marker that steadily rises over a series of three or four consecutive assessments is a fairly convincing sign of disease relapse. This sign will be even stronger if the absolute level of the marker is very high (a value of hundreds or thousands instead of units or tens).

2. Much more solid and important evidence is provided by imaging tests (CT, PET, X-rays, scintigraphy, magnetic resonance, etc). If there is any abnormal finding that was not previously seen during the basic staging examination before the surgical operation, the suspicion of relapse is very strong.

Unfortunately, imaging tests also have limits.

First of all, if there are any metastases, they may be too small to be detected by the imaging examinations currently available. FIGURE 2

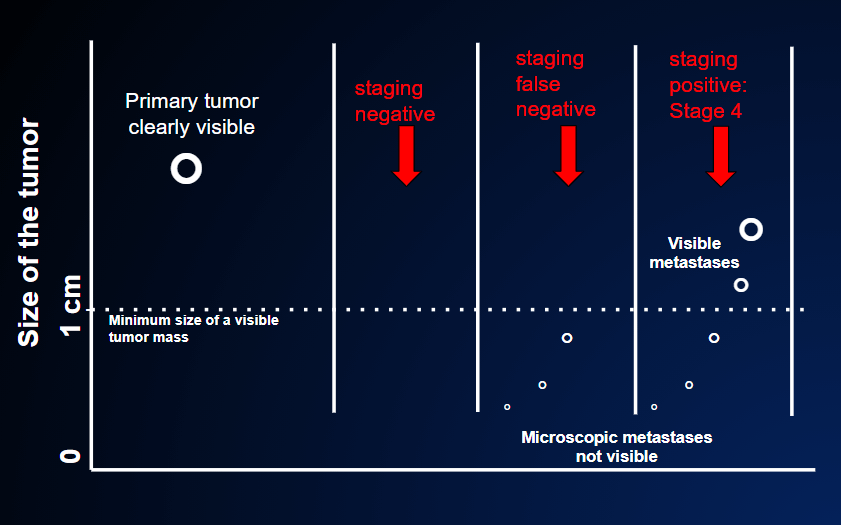

There are 3 possible outcomes of staging, which is the assessment of whether the tumor has spread to distant organs.

In the first case, the staging result is truly negative because the primary tumor has not spread outside the local site of origin as evidenced by negative CT, PET scan and magnetic resonance tests (=no tumor in other organs). After the primary tumor is removed, the patient is cured.

In the second case, the staging result is falsely negative because although the CT, PET scan and magnetic resonance tests are negative (=no tumor in other organs) the primary tumor has already spread outside the local origin, but these small nodules are too small to be revealed by the imaging tests. These tests usually disclose nodules of at least 0.5-1 cm (the dotted line in the figure). After the primary tumor is removed, the patient is not cured. A relapse will become known when these small nodules have grown above that threshold.

In the third case, the staging result is positive (=presence of cancer in other organs) because metastases are already seen by the staging tests: they are already large enough at the time the primary cancer is discovered.

By contrast, imaging examinations may detect suspect nodules that are not actually metastases. Understandably, this causes a lot of worry for both the patient and the doctor.

According to the site and the features of these findings, the specialist has to judge the probability of whether there are metastases or not. He/she must therefore decide whether to carry out further tests, and perhaps take further biopsies, or simply to reassure the patient.

Not all patients understand or accept these limitations of follow-up blood tests and radiological examinations. Hopefully, research will be able to improve the accuracy of the currently available tests or develop more precise and reliable tests in the near future. In this regard, the technology of liquid biopsy is a very good example. Unfortunately, however, this technique is not yet available, as it is still in the experimental phase.

3. Finally, physical examinations. Once the sophisticated blood tests and imaging examinations have proved negative, we may think that physical examination by the doctor is completely useless. While this view may be understandable, we should remember that neither blood tests nor imaging examinations are capable of listening to the patient; and the patient may complain of suspect initial symptoms even when the tests have not detected anything abnormal. Moreover, only the doctor can examine surgical scars or superficial lymph nodes. From the practical point of view, follow-up physical examinations can be carried out perfectly well by the family doctor, in close contact with the oncologist. THE ROLE OF THE FAMILY DOCTOR.